Cultural bias may generate error in science, with adverse effects beyond science.

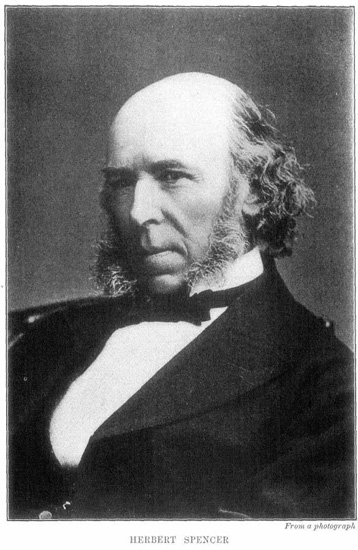

In the late 1800s self-styled philosopher Herbert Spencer claimed that the facts of evolution supported a laissez-faire social ideology, a doctrine now often inappropriately attributed to Darwin (Spencer 1851, 1852a, 1852b, 1864). He claimed that nature exhibited inherent values, such as competition-based progress, that should guide human society. His views were sharply criticized by philosopher G.E. Moore (1903), who famously called Spencer's error the naturalistic fallacy. Nature's patterns or processes do not exhibit inherent ideals, he noted. Natural selection, despite the label, exercises no authentic choice, or intent. Spencer's error may still be found today when someone argues that some value or moral principle is justified because a certain trait is (they claim) universal, or innate, or reflects "human nature." But frequency does not establish value. Nor does evolutionary history justify itself. Facts alone cannot yield values. Accordingly, science cannot "discover" particular moral or ethical goals, even it can explain the observed behavior. The values come from humans and their discourse.

In the late 1800s self-styled philosopher Herbert Spencer claimed that the facts of evolution supported a laissez-faire social ideology, a doctrine now often inappropriately attributed to Darwin (Spencer 1851, 1852a, 1852b, 1864). He claimed that nature exhibited inherent values, such as competition-based progress, that should guide human society. His views were sharply criticized by philosopher G.E. Moore (1903), who famously called Spencer's error the naturalistic fallacy. Nature's patterns or processes do not exhibit inherent ideals, he noted. Natural selection, despite the label, exercises no authentic choice, or intent. Spencer's error may still be found today when someone argues that some value or moral principle is justified because a certain trait is (they claim) universal, or innate, or reflects "human nature." But frequency does not establish value. Nor does evolutionary history justify itself. Facts alone cannot yield values. Accordingly, science cannot "discover" particular moral or ethical goals, even it can explain the observed behavior. The values come from humans and their discourse.

Spencer was misguided on an even more fundamental level. His biology was ultimately shaped by his own political beliefs. He did not extract values from nature, so much as inscribe them into his scientific descriptions. He rendered nature as a biologized version of the social ideology he endorsed. Scientists may succumb to this mistake, known as the naturalizing error, without realizing it, when their cultural perspective functions like a conceptual blindspot (Allchin 2008). Portraying nature as fundamentally competitive and ruthless — or even as morally ideal — may be shaped more by our economic and cultural views than by critical interpretation of the evidence.

Spencer was misguided on an even more fundamental level. His biology was ultimately shaped by his own political beliefs. He did not extract values from nature, so much as inscribe them into his scientific descriptions. He rendered nature as a biologized version of the social ideology he endorsed. Scientists may succumb to this mistake, known as the naturalizing error, without realizing it, when their cultural perspective functions like a conceptual blindspot (Allchin 2008). Portraying nature as fundamentally competitive and ruthless — or even as morally ideal — may be shaped more by our economic and cultural views than by critical interpretation of the evidence.

Download supplemental essay:  "Social UnDarwinism"

"Social UnDarwinism"