| |

Background

|

|

It is 1948. World War II has ended. Now, three years later, an era of post-war prosperity seems upon us. We look to the promise of science and technology, so important in winning the war, in providing a better future. As one emblem of that success, Paul Muller receives a Nobel Prize for his discovery of the insecticidal properties of DDT. |

|

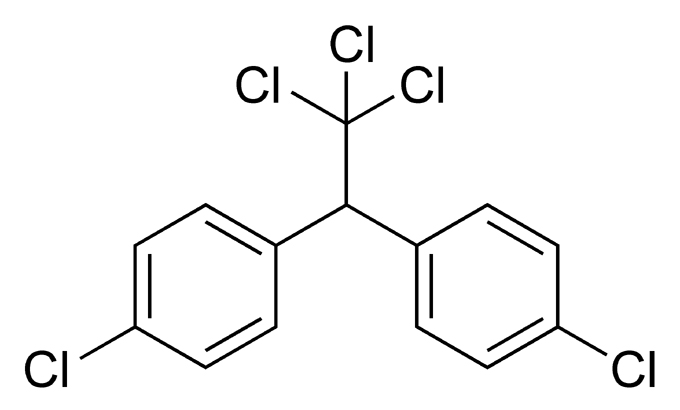

DDT (dichloro-dipheynl-tricholoethane) was first synthesized 1873. But at that time, it was just another molecule, with no notable qualities.

|

|

In 1935, Muller, a researcher at Geigy (Basle, Switzerland), began looking for chemicals that might help control Colorado potato beetles. In 1939, he announced finding the insecticidal properties of DDT. The Swiss notified the U.S. government and secretly sent them a sample on November 3, 1942. |

|

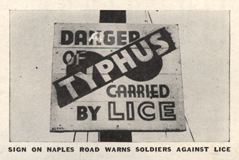

U.S. military research on pesticides -- against typhus louse and mosquitoes -- had been underway since 1941 (by the medical branch of OSRD). Disease was no peripheral military issue: 2.5 million had died of typhus in World War I. Malaria was now a concern especially in the Pacific theater. The National Research Council had, since 1940, been organizing research among industries and foundations for an effective mosquito repellant. DDT research in Florida now focused on "military" effectiveness. By Feb 1943, DDT was shown to be one hundred times more toxic to mosquito larvae than any alternative.

|

|

The Nobel Prize celebrates the subsequent events. When typhus appeared near end of the War, the citation notes, despite other research on pesticides, DDT came as "deliverance", as a "deus ex machina."

"In October of 1943 a heavyoutbreak of typhus occurred in Naples and the customary relief measures proved totally inadequate. General Fox thereupon introduced DDT treatment with total exclusion of the old, slow methods of treatment. As a result, 1,300,000 people were treated in January 1944 and in a period of three weeks the typhus epidemic was completely mastered. Thus, for the first time in history a typhus outbreak was brought under control in winter. DDT had passed its ordeal by fire with flying colours."

"In DDT..., we also possess an extremely valuable remedy in the fight against malaria, this the most widespread of all contagious diseases which yearly affects about 300,000,000 people and causes a yearly death rate of at least 3,000,000."

Accordingly, World War II was the first war where more soldiers died of wounds than of disease.

|

|

"Furthermore," the Nobel citation notes "[DDT] is cheap, easily manufactured and exceedingly stable. A surface treated with DDT maintains its insecticidal proprerties for a long time, up to several months." It exemplifies the other great achievement of science during the war: penicillin, radar, and nuclear energy:

As the Nobel Foundation notes, "The story of DDT illustrates the often wondrous ways of science when a major discovery has been made. A scientist, working with flies and colorado beetles discovers a substance that proves itself effective in the battle against the most serious diseases in the world. Many there are who will say he was lucky, and so he was. Without a reasonable slice of luck hardly any discoveries whatever would be made. But the results are not simply based on luck. The discovery of DDT was made in the course of industrious and certainly sometimes monotonous labour; the real scientist is he who possesses the capacity to understand, interpret and evaluate the meaning of what at first sight may seem to be an unimportant discovery."

|

|

A 1944 Geigy press release, reported "Now It Can Be Told":

". . . Geigy believes that it has the support of the United States Department of Agriculture in predicting that the general commercial production of Gerasol, when the military needs have been accommodated, will open the way to what may be regarded as a revolution in the economy of agriculture and in the quantity of the world's food output...."

|

|

Indeed, here we see DDT sprayed on Long Island beaches in 1945. It is also being used in agriculture, sprayed on fields and sometimes from the air. It is far less poisonous than the pre-WWII arsenic compounds.

|

|

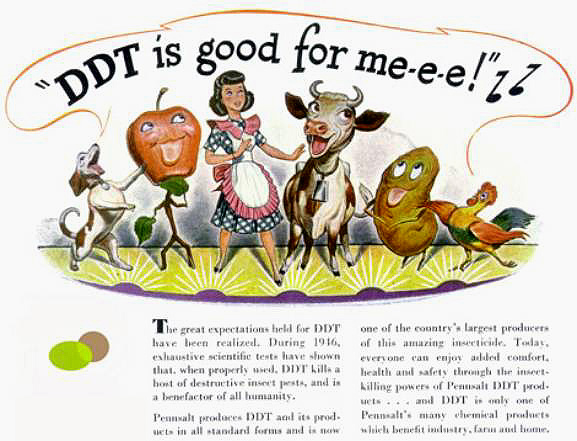

As exemplified, too, in a Time magazine ad for DDT, we can look forward to a new era of prosperity and peace guided by science and technology.

|

|

Fast forward, now, to 1962. DDT and other pesticides developed in the past several decades (aldrin/dieldrin, dinitrophenol [DNP], 2,4-D and FCCP, among others) are in the news again, but now as a target of criticism. Nature writer Rachel Carson has written an emotional plea about their harm to wildlife, humans health and the balance of nature.

|

|

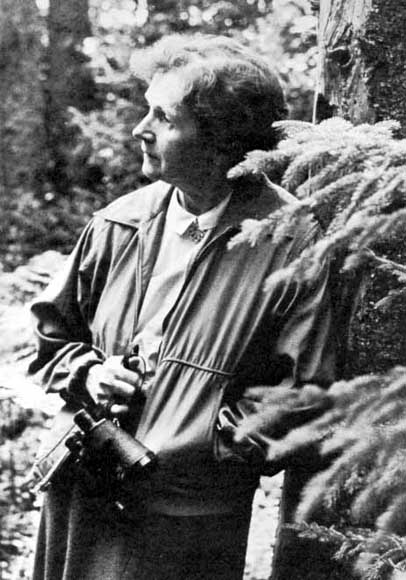

Carson has a unique dual expertise: in biology and in writing.

As a youth in western Pennsylvania, she became interested in nature. In college, a required science course led her to major in biology, and later she earned a masters of marine biology at Johns Hopkins University. For her thesis, she dissected embryos, prepared slides, and described development of kidney in catfish. Her skill as a writer appeared early: her first writing award was at age 11, and she was encouraged by her mother. |

|

In her early career, she was a writer for US Fish & Wildlife Service (only the 2nd woman hired there in non-secretarial role). Later she wrote many popular and award-winning books about the sea, expressing a fascination with its creatures. The royalties from her book allowed her to retire from the government to become a full-time writer.

|

|

In 1958, Carson received a letter from Olga Hutchins, a birdwatcher in Massachusetts, who had written earlier to the Boston Herald, complaining about DDT spraying:

"The mosquito control planes flew over our small town last summer. Since we live close to the marshes, we were treated to several lethal doses as the pilot criss-crossed our place. ... The 'harmless' shower bath killed seven of our lovely songbirds outright. We picked up three dead bodies the next morning right by our door. ... All thse birds died horribly, and in the same way. Their bills were gaping open, and their splayed claws were drawn up to their breasts in agony."

The DDT, mixed w/ fuel oil, seemed not to be "harmless," as state officials had told her.

|

|

Hutchins had written to Rachel Carson (an acquaintance), asking who to contact in the government. After several inquiries, Carson realized that many knew about DDT, but scientific knowledge was not guiding policy decisions. She decided to write about pesticides herself. In a letter, she noted that "pesticides represented an "alarming threat to human welfare, and also the basic balance of nature on which human survival ultimately depends." In another letter to a friend several months later she confided, "there would be no peace for me if I kept silent."

What began as a prospective article for Reader's Digest was turned down. It expanded into book length. Carson was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1957 (just before starting work on book). In late 1958, her mother (with whom she had been very close) died. Then her sister died, and she assumed responsibility for raising her nephew. In 1960, she had a radical mastectomy.

|

|

The book had begin with the working title: "The Control of Nature," but changed to "Man Against the Earth," then "Dissent in Favor of Man." Editor Paul Brooks suggested using a chapter title, "Silent Spring."

|

|

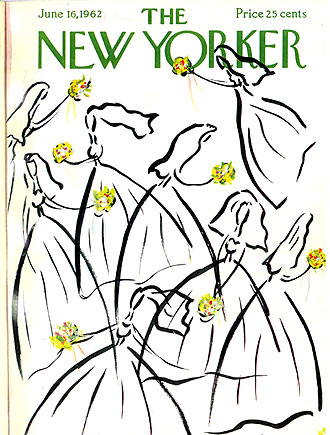

Carson's work first appeared as a series of three articles in New Yorker magazine, comprising about 1/3 of the book. That was where President John F. Kennedy read it. Impressed by its claim, he has assembled a commision to study the problem.

|

|

Carson profiles many facets of DDT, besides it ability to kill disease and agricultural pests. DDT is persistent in the environment. It seems to affect wildlife and non-target species. It is a contact toxin to animals, and can possibly accumulate in the food chain, leading to neurological effects. Carson claims it is a carcinogen, possibly poisoning food. For Carson, alternative pest management strategies are available and need to be considered. We look to the President's Advisory Committee on Pesticides for guidance.

For more context, see the historical supplements.

|

| |

Text by Douglas Allchin. || last revised Nov. 15, 2006

|

|